Shingles, also known as herpes zoster, is a painful viral infection caused by the reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) – the same virus that causes chickenpox. After a bout of chickenpox, the virus lies dormant in nerve cells. Years, even decades later, it can reactivate and travel along nerve pathways to the skin, causing the characteristic rash of shingles. What makes shingles unique and often diagnostically helpful is its tendency to follow a specific pattern: the dermatome map.

Understanding the concept of a dermatome map is crucial to understanding shingles, its symptoms, and how it’s diagnosed and treated. This article will delve into the intricacies of dermatomes, explore how shingles manifests along these pathways, and discuss the implications for diagnosis, treatment, and potential complications.

What is a Dermatome Map?

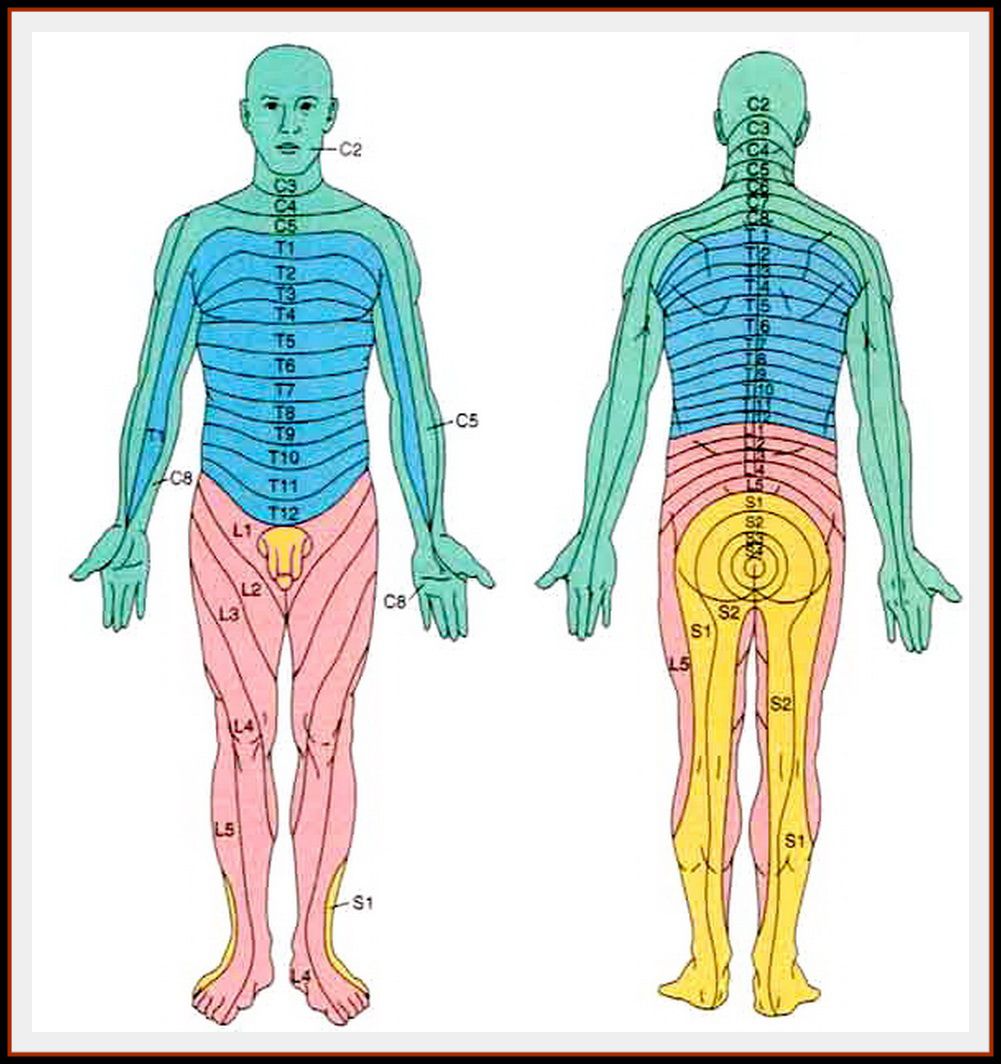

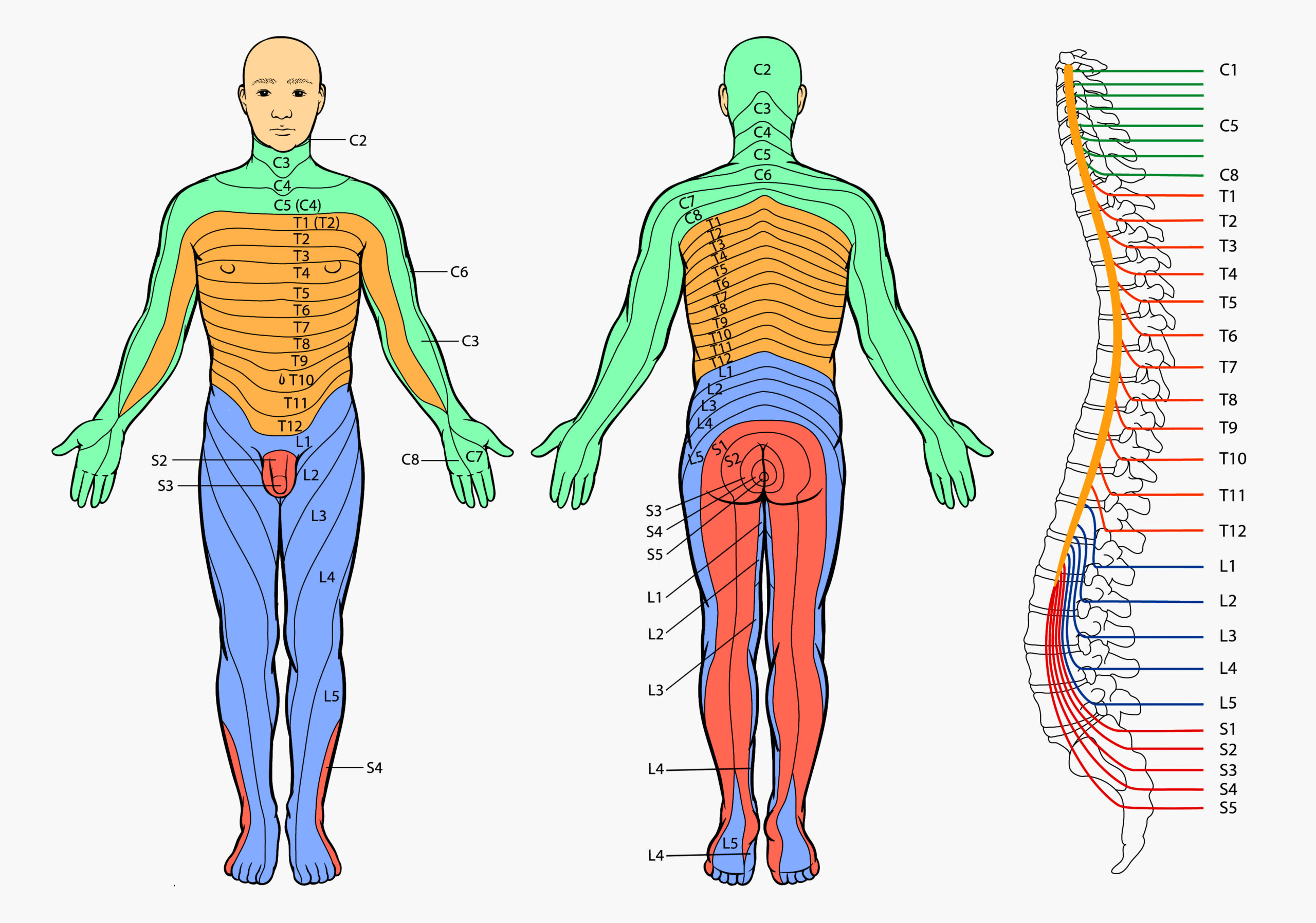

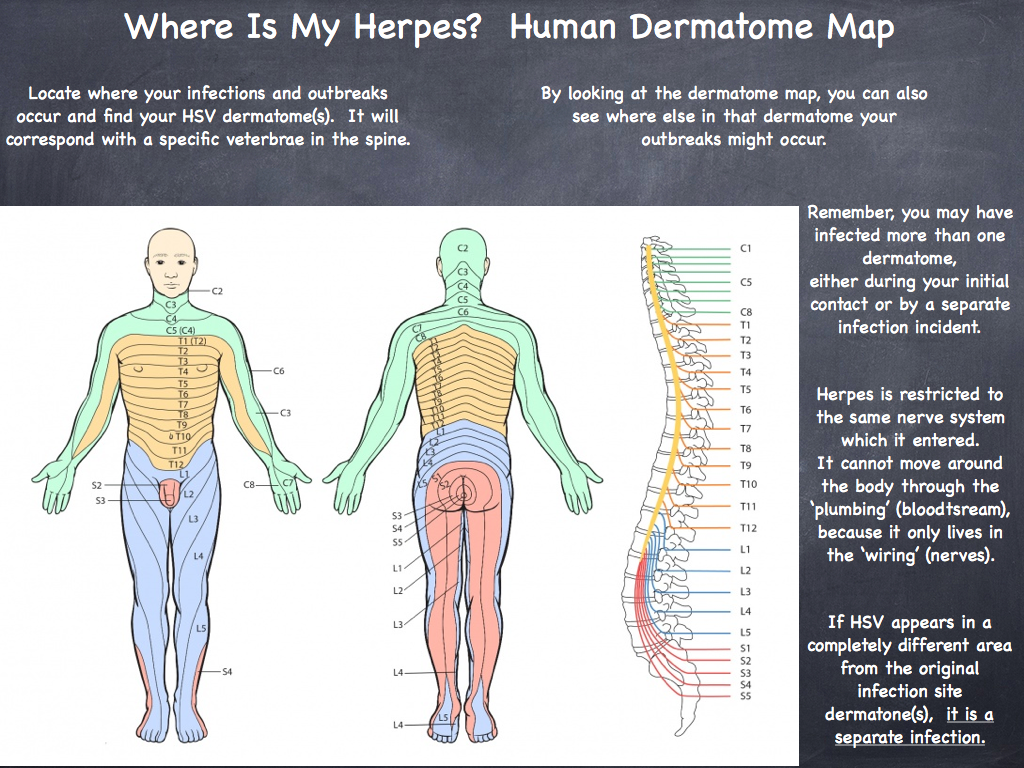

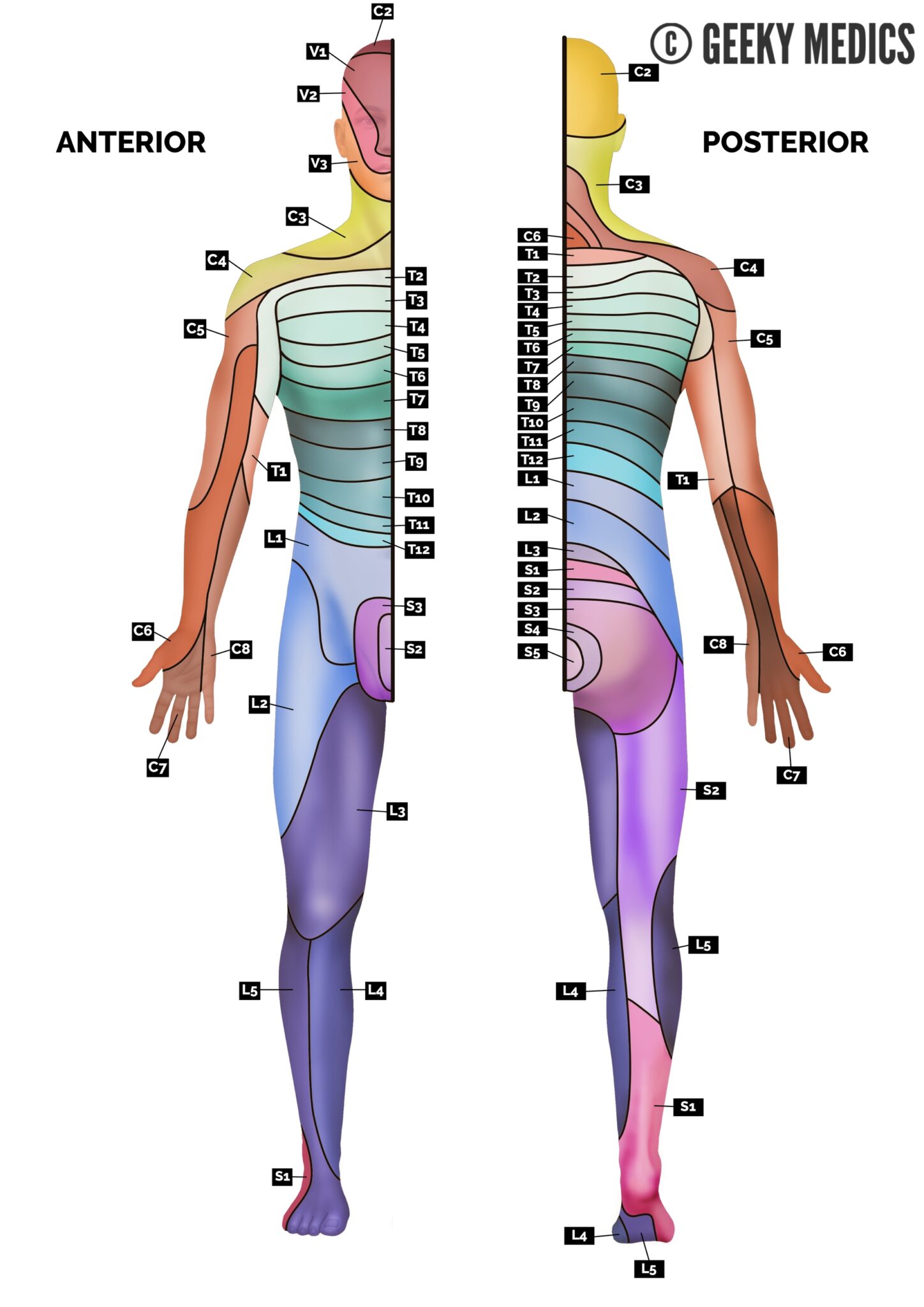

A dermatome is an area of skin that is primarily supplied by a single spinal nerve. Each spinal nerve originates from the spinal cord and branches out to innervate specific regions of the body. Imagine the body as a layered cake, with each layer representing a different dermatome. These dermatomes form a predictable pattern across the body, creating a map that links specific skin areas to specific nerve roots in the spinal cord.

This "dermatome map" is an essential tool in neurology and dermatology. It helps healthcare professionals:

- Identify the location of nerve damage: By observing sensory changes (like numbness or pain) in a specific dermatome, doctors can pinpoint the affected nerve root in the spinal cord.

- Diagnose neurological conditions: Conditions like spinal disc herniation, spinal cord injuries, and nerve root compression can often be diagnosed based on dermatome involvement.

- Understand the spread of certain infections: As we’ll see with shingles, some infections, like VZV, preferentially affect specific dermatomes.

The Role of Dermatomes in Shingles

When VZV reactivates, it doesn’t spread randomly throughout the body. Instead, it travels along the nerve pathway of a single dermatome, typically affecting one side of the body. This is why shingles characteristically presents as a unilateral, band-like rash that follows the path of a specific dermatome.

The most commonly affected dermatomes in shingles are those in the thoracic region (chest and abdomen), followed by the trigeminal nerve (face, particularly around the eye). However, shingles can affect any dermatome, including those in the lumbar region (lower back), sacral region (buttocks and genitals), and even the cervical region (neck and shoulders).

Recognizing Dermatome Map Shingles: Symptoms and Progression

The symptoms of shingles often begin with pain, itching, tingling, or burning in the affected dermatome. This prodromal phase can last for several days before the appearance of any visible rash. The pain can be quite intense and may be mistaken for other conditions, such as a heart attack (if in the chest region) or appendicitis (if in the abdominal region).

Following the prodromal phase, the characteristic rash appears. It typically begins as small, red bumps (macules) that quickly develop into fluid-filled blisters (vesicles). These vesicles are grouped together in clusters, forming a band-like pattern that closely follows the affected dermatome.

Key characteristics of dermatome map shingles include:

- Unilateral Distribution: The rash is almost always confined to one side of the body.

- Dermatomal Pattern: The rash follows the path of a specific dermatome, forming a distinct band or stripe.

- Vesicular Rash: The rash consists of fluid-filled blisters that are often painful.

- Preceding Pain: Pain, itching, or tingling often precedes the appearance of the rash.

Over the next few days, the vesicles become cloudy and may break open, forming ulcers. These ulcers eventually scab over and heal, typically within 2-4 weeks. However, even after the rash has healed, some people may experience persistent pain in the affected dermatome, a condition known as postherpetic neuralgia (PHN).

Diagnosis: Spotting the Dermatomal Pattern

The diagnosis of shingles is usually made clinically, based on the characteristic dermatomal rash and accompanying symptoms. The healthcare professional will take a thorough history, asking about any preceding pain, itching, or tingling, and will carefully examine the rash.

The dermatome map is a crucial diagnostic tool. By observing the distribution of the rash, the doctor can identify the affected dermatome and confirm the diagnosis of shingles. In cases where the rash is atypical or the diagnosis is uncertain, laboratory tests may be performed to confirm the presence of VZV. These tests may include:

- Viral culture: A sample from the blisters is cultured to detect the presence of VZV.

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR): This test detects VZV DNA in a sample from the blisters or blood.

- Direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) test: This test uses fluorescent antibodies to detect VZV antigens in a sample from the blisters.

Treatment: Managing Symptoms and Preventing Complications

The primary goals of shingles treatment are to:

- Reduce the severity and duration of the rash.

- Relieve pain.

- Prevent complications, such as postherpetic neuralgia.

Antiviral medications, such as acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir, are the mainstay of treatment. These medications work by inhibiting the replication of VZV, thereby reducing the severity and duration of the rash. They are most effective when started within 72 hours of the onset of the rash.

Pain management is also an important aspect of shingles treatment. Over-the-counter pain relievers, such as acetaminophen and ibuprofen, may be sufficient for mild pain. However, more severe pain may require prescription pain medications, such as opioids or nerve pain medications (e.g., gabapentin, pregabalin).

Other treatments that may be used to manage shingles symptoms include:

- Calamine lotion: To soothe itching.

- Cool compresses: To relieve pain and inflammation.

- Topical antibiotics: To prevent secondary bacterial infections.

Complications: Beyond the Rash

While shingles is usually a self-limiting condition, it can sometimes lead to complications, particularly in older adults and those with weakened immune systems. These complications can include:

- Postherpetic Neuralgia (PHN): This is the most common complication of shingles. It is characterized by persistent pain in the affected dermatome that lasts for months or even years after the rash has healed. PHN can be debilitating and can significantly impact quality of life.

- Ophthalmic Shingles: This occurs when shingles affects the trigeminal nerve, specifically the ophthalmic branch, which supplies the eye. Ophthalmic shingles can cause serious eye complications, including vision loss.

- Herpes Zoster Oticus (Ramsay Hunt Syndrome): This occurs when shingles affects the facial nerve, causing facial paralysis, hearing loss, and vertigo.

- Bacterial Infections: The blisters of shingles can become infected with bacteria, leading to cellulitis or impetigo.

- Disseminated Shingles: In rare cases, shingles can spread beyond the affected dermatome and affect other parts of the body. This is more common in people with weakened immune systems.

Prevention: Vaccination is Key

The best way to prevent shingles and its complications is through vaccination. There are two shingles vaccines available:

- Shingrix: This is a recombinant subunit vaccine that is highly effective in preventing shingles and PHN. It is recommended for adults aged 50 years and older, even if they have had shingles before.

- Zostavax: This is a live attenuated vaccine that is less effective than Shingrix and is no longer available in the United States.

Vaccination significantly reduces the risk of developing shingles and, if shingles does occur, it tends to be less severe and less likely to result in complications.

Conclusion: The Importance of Understanding Dermatome Map Shingles

Shingles, with its characteristic dermatomal rash, is a painful and potentially debilitating condition. Understanding the concept of dermatomes and how VZV reactivates along these pathways is crucial for accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and prevention of complications. By recognizing the dermatomal pattern of the rash, healthcare professionals can quickly identify shingles and initiate appropriate treatment. Vaccination remains the most effective way to prevent shingles and protect against its potential long-term consequences. If you suspect you have shingles, it is important to seek medical attention promptly to begin treatment and minimize the risk of complications. Early intervention is key to a more comfortable recovery and a reduced risk of persistent pain.